Sudan's Famine Overwhelms Aid Effort

July 7, 1998

by Karl Vick, Washington Post Foreign Service

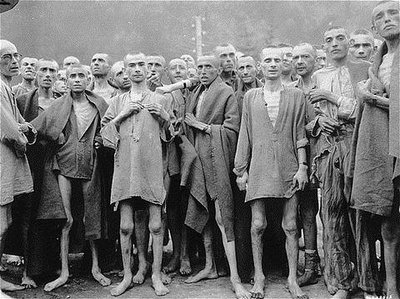

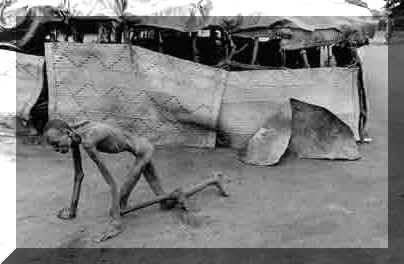

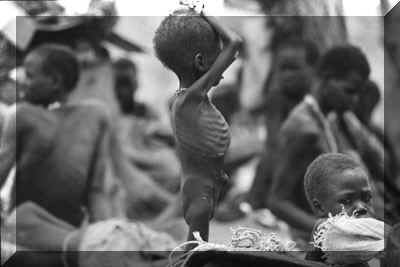

AJIEP, Sudan--As the gate is about to close for the night on the feeding center here, near-lifeless bodies start turning up everywhere. Three have collapsed just outside the reed walls of the compound, human skeletons so thin they look two-dimensional against the ground.

Three, then four, then five, then, somehow, eight others have been carried inside and laid among the swarm of gaunt people still strong enough to beckon medical workers who have spent the day ministering to the hundreds gathered outside this place that has food.

The workers move from body to body, feeling for a pulse, crumbling high-calorie biscuits into palms, pouring sugar water from gourd to mouth. The impossibly sunken cheeks of a man too weak to hold his head up by himself fall deeper into his face as he slurps.

"This is the worst," said Henry Verbeke, who has happened on the scene while making the rounds of the seven feeding centers run by the international aid agency Doctors Without Borders in southern Sudan. "The number of children, the number of adults and the general situation" -- he opens his hands toward a scene out of Dante -- "you can see for yourself."

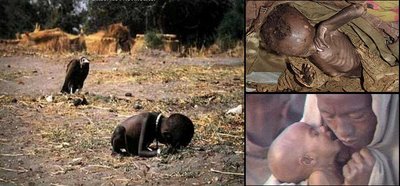

Four months after aid agencies issued warnings of impending famine in southern Sudan -- and two months after they marshaled public opinion in the name of heading it off -- starvation has arrived regardless. Across a vast region unsettled by civil war and erratic weather, the United Nations now says, 1.2 million people are at risk of death from hunger. The total is four times the population declared at risk when the alarm was sounded two months ago.

Since then, U.N. cargo planes have flown almost constantly, dropping bags of cereals and high-calorie mix at three times any previous rate. By all accounts it remains too little.

"It's getting worse," said Charlotte Kragboll, a Danish nurse who spends her days trying to cull the most dire cases from hundreds who gather in 100-degree heat outside the gates in Ajiep. The village is located in Bahr el Ghazal, the southwest Sudanese province hardest hit by food shortages. Across much of Sudan, cultivation has been disrupted by fighting between rebels seeking independence from the country's fundamentalist Islamic regime.

In the south, where the region's African, mostly Christian or animist population has been battling Sudan's Muslim, northern Arab-dominated government for most of four decades, the disruption was profound. A former rebel commander swept through part of Bahr el Ghazal, stealing cattle and looting grain stores. When he returned to the rebel side, his place was taken by the government's Popular Defense Force -- Arab horsemen who gallop through the Dinka tribe's villages burning, shooting and frightening people off their land.

"The people left without anything in their hands," said Zefferino Ayri, the local chief.

When the Dinkas returned, the planting season had passed and weather patterns associated with El Nin o delayed rains that normally nourish pasture lands and river fishing. The annual lean time that normally lasted about a month before the August harvest started in April this year. In places, there will be no harvest to end it.

"They are living on leaves of the trees," Ayri said of residents who now look skyward not for rain -- which still has not come in significant amounts here -- but for the C-130 cargo planes that drop food.

The emaciated crowds outside the Doctors Without Borders compound testify to the inadequacy of the airlift to date. Workers dispense only a few boxes of fortified biscuits and a small bag of "high-energy porridge" called Unimix to each family once a week. General food distribution remains the province of the U.N. World Food Program, with an effort called Operation Lifeline Sudan. Independent agencies such as Doctors Without Borders operate what are called "supplementary feeding centers."

"Supplementary to what, you might ask," a nurse said, after tending to a wraith carried by his brother. "The problem is we can't give him a full ration. If we can't give him a full ration, it's the fault of the international community."

Said Lu Nakel, a German doctor: "The food from outside which is supposed to be here is not here."

U.N. officials acknowledge the shortfall. The last food drop at Ajiep, on June 7, brought enough food for 18 days. But repairs grounded the equivalent of one aid plane for an entire month, and the U.N. airlift has 75 locations to supply. When the food in Ajiep was scheduled to run out two weeks ago, resupply was still weeks away.

The failure underscores the tenuous nature of the rescue operation, a permanent bureaucracy that has been unable to keep pace with a rolling disaster it has been predicting in general terms since last September.

The World Food Program managed to raise only 50 percent of its appeal from donors last year, according to spokeswoman Brenda Barton, who said related programs operating in Sudan fared even worse. Blame fell on "donor fatigue" associated with a region that has had food shortages since Operation Lifeline Sudan was established in 1989, when a quarter-million people died of hunger in Bahr el Ghazal.

"I think the people of the world really want to help Sudan, but they're tired," said Rep. Tony P. Hall (D-Ohio). Hall, who is Congress's specialist on hunger issues, made an indignant call for international assistance after touring the area last month, saying the malnutrition he saw in Ajiep was the most life-threatening "since Ethiopia," where famine killed a million people in the mid-1980s.

In Sudan, a bad situation grew worse in February and March, when the government banned relief flights. After an international outcry, the lid was slowly lifted, and by June the United Nations had access to all of Sudan -- but it lacked the planes to reach it. The airlift complement has gradually grown from one to four C-130s, but Operation Lifeline Sudan is still awaiting government permission to add four Ilyushin cargo planes that have twice the C-130s' 16-ton capacity.

In the meantime, death rates in southwestern Sudan steadily rose as prospects steadily dimmed. By late June, the situation qualified for a term the United Nations had carefully avoided until late last month: famine.

"There are many places in Bahr el Ghazal that meet the definition of famine," Barton said.

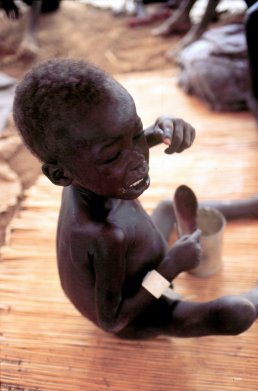

Ajiep is one of them. The center here has intensive feeding facilities only for children under 5, and only for 50 of those. A place on the waiting list is determined by lifting the child into what looks like a jolly jumper that hangs from a scale instead of a door frame. Technically, children who weigh less than 70 percent of normal for their height qualify, but here the standard has dropped to 60 percent. If there is room, they go to a separate compound for seven feedings of enriched milk a day.

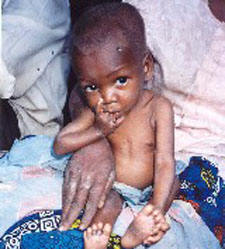

Even so, four in 10 are losing weight, and on average at least one dies per day. The quiet, orderly center is filled with terrifyingly thin infants suckling young breasts so withered the child will hold one in two hands and fold it toward him.

"We work and we work and they don't get anywhere," Kragboll, the nurse, said with a dismayed look. A few moments earlier, rounding a corner outside the main compound, she had come upon a thin, gaunt child curled under a bush. Bright white foam billowed from the child's nose and mouth. Another aid worker lifted her into his arms and scrambled inside. Kragboll felt again and again for a pulse.

"It's too late," she said, and looked around. "Where's the mother of the child?"

The mother was dead. So was the father, a blind man. Their daughter Aluat Anei Manong, 8, had walked to the feeding center with an aunt. The girl's body was carried away on a stretcher fashioned from empty food sacks, one marked UNICEF, the other USA.

At the crowded graveyard where 33 were buried the previous week, three men set again to digging. The hole was deep, but not long, because the Dinka believe the dead should be buried with the legs folded, said Salva Atak Kuol, who watched fromone side.

The tribe also forbids burial with jewelry, so after laying Aluat to rest, one of the men reached down and pulled two strands of beads from her neck.

Then he and the other gravediggers turned and began to paddle the sandy soil back into the hole, being careful to keep their backs to the grave as they worked.

"It is a sort of goodbye," Kuol said.

Crying baby in Sudan.

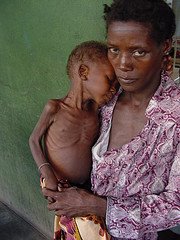

Woman feeding a baby. 1997

Supplies for Sudan. Not enough for over 2 million People.

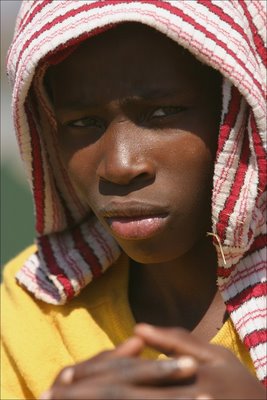

Crying.....