A Place of Sorrow and Shattered Dreams

Photo essay: Ethiopia food crisis

Photos by Hege Opseth Norwegian Church Aid/ACT InternationalText by Hege Opseth and Callie Long

Driven by hunger and a promise of good land for farming and grazing they came to Showa in their thousands. Finding shelter in an abandoned military camp, they all came in hope. Instead, what 26,000 people from the drought-stricken Harar region found over the course of half a year, were shattered dreams and unimaginable sorrow, despair and hunger, funerals and in the end, a loss of hope.

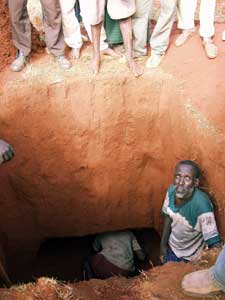

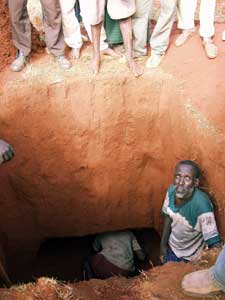

"Four children will be buried tonight", say the sextons from the cemetery - all relatives of the children who died over the weekend. Children are buried in mass graves. Wild roses thickets are laid on top of the graves to deter animals from scavenging. "One cemetery is already full."

The haunted look of hunger is everywhere. Listless children, too exhausted to care about the flies that throng and settle everywhere, watch as their mothers try to help, their thin cries mixing with the muted despair uttered by their mothers. "The worst thing about this life is to see how the children suffer. They are very ill", says Fatoma Alisho.

"I am going to die", says Tofokara. She too has lost hope. "Only God knows what will happen … if we will get food, she says." Further away from Showa, in the Shinile region, some hours drive from Dire Dawa into the desert lies Asivuli. The heat is extreme during daytime. At night, temperatures plummet. Members of Action by Churches Together (ACT) International are working on providing shelter for the people who have fled their drought stricken regions, only to find themselves stranded in the desert. Meanwhile, meagre rations from the United Nation's World Food Program keep people alive.

Famine spares no one.

Members of ACT International, who have joined forces under the umbrella of the Joint Relief Partnership (JRP) to tackle the growing humanitarian emergency in Ethiopia, estimate conservatively that about 6,2 million people are trapped in the cycle of famine and hunger. This latest emergency in Ethiopia has been brought on by a number of factors - recurring and lingering drought in some districts (known as woredas), sporadic rainfall or no rainfall at all and the resulting decimation of entire crops.

In an ideal world those suffering from hunger would be taken to hospital where they would be fed small portions of food five times a day to help them regain their strength. The reality is that millions of Ethiopians will never receive this kind of help - food is scarce and hospitalisation, an unimaginable form of assistance and relief.

Hundreds of people arrive daily in Showa, hoping against all odds that they will somehow survive the disaster.

The dream of a better future has ended here at Showa in an abandoned military camp - a place where hope is hard to find, but grief and sorrow not. The 'lucky ones' sleep in the condemned barracks. The rest of the people sleep outside on the ground. And they wait…

Photos by Hege Opseth Norwegian Church Aid/ACT InternationalText by Hege Opseth and Callie Long

Showa, Ethiopia, January 8, 2003

Driven by hunger and a promise of good land for farming and grazing they came to Showa in their thousands. Finding shelter in an abandoned military camp, they all came in hope. Instead, what 26,000 people from the drought-stricken Harar region found over the course of half a year, were shattered dreams and unimaginable sorrow, despair and hunger, funerals and in the end, a loss of hope.

"Four children will be buried tonight", say the sextons from the cemetery - all relatives of the children who died over the weekend. Children are buried in mass graves. Wild roses thickets are laid on top of the graves to deter animals from scavenging. "One cemetery is already full."

The haunted look of hunger is everywhere. Listless children, too exhausted to care about the flies that throng and settle everywhere, watch as their mothers try to help, their thin cries mixing with the muted despair uttered by their mothers. "The worst thing about this life is to see how the children suffer. They are very ill", says Fatoma Alisho.

"I am going to die", says Tofokara. She too has lost hope. "Only God knows what will happen … if we will get food, she says." Further away from Showa, in the Shinile region, some hours drive from Dire Dawa into the desert lies Asivuli. The heat is extreme during daytime. At night, temperatures plummet. Members of Action by Churches Together (ACT) International are working on providing shelter for the people who have fled their drought stricken regions, only to find themselves stranded in the desert. Meanwhile, meagre rations from the United Nation's World Food Program keep people alive.

Famine spares no one.

Members of ACT International, who have joined forces under the umbrella of the Joint Relief Partnership (JRP) to tackle the growing humanitarian emergency in Ethiopia, estimate conservatively that about 6,2 million people are trapped in the cycle of famine and hunger. This latest emergency in Ethiopia has been brought on by a number of factors - recurring and lingering drought in some districts (known as woredas), sporadic rainfall or no rainfall at all and the resulting decimation of entire crops.

In an ideal world those suffering from hunger would be taken to hospital where they would be fed small portions of food five times a day to help them regain their strength. The reality is that millions of Ethiopians will never receive this kind of help - food is scarce and hospitalisation, an unimaginable form of assistance and relief.

Hundreds of people arrive daily in Showa, hoping against all odds that they will somehow survive the disaster.

The dream of a better future has ended here at Showa in an abandoned military camp - a place where hope is hard to find, but grief and sorrow not. The 'lucky ones' sleep in the condemned barracks. The rest of the people sleep outside on the ground. And they wait…

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home